John Berger

In 1954 at the age of four I began learning the piano with the delightful Miss Kinsey. I continued through to the upper end of high school and entered a music course at a university in Western Australia. Despite my love of the keyboard, by this time I had given up piano studies. While at residential college, I met several guitarists and became enamoured with folk guitar, eventually playing with friends at local venues. Later, while performing in a folk band, I became attracted to the sound of the fiddler, which began my life-long journey with the violin.

Then I discovered Shinichi Suzuki’s book, Nurtured by Love. A revelation!

Following my deep love of classical music, I studied violin with several teachers in Western Australia, including Suzuki teachers Pauline and Ian Dawson, Daphne Murname, and others, joining the Suzuki teaching world.

After some years, I'd progressed sufficiently to begin teaching in rural WA and Perth until the time Ian Dawson passed away, causing me to consider undertaking more studies. This was a busy time for us, with a good number of students, attending a great number of workshops, events and concerts in Perth, Sydney and one in Singapore.

I was accepted into Suzuki's institute, and in 1986 we left for Matsumoto.

Other Places I have lived since Japan: UK

Instrument studied in Japan: Violin

Dates you were in Japan to study with Shinichi Suzuki: In Japan with Shinichi Suzuki Feb 1987 to Mar 1990; then summer schools or visits to Matsumoto and other teachers 1993; 1995; 1996; 1997; 1999; 2000; 2004; 2006; 2007; 2017 mostly for 2 or 3 weeks.

Years and locations of workshops with Dr. Suzuki that were outside of Japan: Singapore 1983

Memories

I’d been teaching Suzuki violin for several years. Sadly, my friend and Suzuki mentor and teacher Ian died, leaving me with the prospect of teaching a few of his advanced students. I felt more training was needed. "We could go to study with Suzuki in Japan," I said to Allie, knowing we had little money at the time and that it would entail taking our three children out of school to Japan - without any knowledge of the language. It was a leap into the unknown.

I was 36. Originally, I planned to study with Shinichi Suzuki for a year to improve my teaching and playing, but soon saw the value of studying for a longer time, with the prospect of graduating. It wasn’t an easy decision in view of our children’s education and our limited finances and would probably involve some hardship.

With my wife Allie and our three school age children, it probably took over a year to plan our trip. Allie, studying for her education degree, took out a small university loan of $2000, hoping English teaching would pay our way. We sold our house, paid off the mortgage and corresponded with the Suzuki office about accommodation, living conditions, registration, visas and asking questions about what to expect. We got 1 year student visas, which required renewing every year.

Somewhat bewildered and not knowing where the platform for Matsumoto was, I have an image in my mind of us standing on the pavement outside Shinjuku station with 14 articles of baggage, as the daytime crowd flowed around us in obvious amusement. We’d been dropped there dazed and confused about how to get to Matsumoto. After plumbing the labyrinth of Shinjuku Eki’s levels we found the right train and boarded with our baggage, not knowing that it could be sent separately. Michiko met us and helped get our family to the place we were to stay.

During the three years we lived in two apartments and a little garden house. In contrast with our usual living conditions in Australia they were tiny and rather basic, but despite the difficulties, we treated it as an interesting adventure. It was a longish bike ride to the Suzuki Institute (Kaikan) from the first apartment in Yoshikawa. Next, we were able to find the small garden house near Matsumoto castle. Our final apartment was in South Matsumoto, owned by a gallery owner with whom we remain friends to this day. We travelled on bikes, motorbikes and finally in a car to manage the cold and snowy winter weather.

Coming from the hot summers of Australia, we loved the snow and ice from the start. The surrounding area of Matsumoto is very beautiful in all seasons, especially the mountains. All food seemed to be saturated in soya sauce, yet we grew an enduring love of Japanese cuisine. Some of the other students have become lifelong friends, despite living in far flung countries. Our two boys went to Kaichi Shōgakkō (primary school) and joined the baseball and karate clubs, eventually becoming quite fluent in Japanese.

We paid our costs and fees by teaching English around Matsumoto and nearby towns.

We learned much of our playing and teaching skills at daily group class with Dr Suzuki, which often focused on tone production and the use of the bow. Together with the daunting private lessons, they provided direction for practice and improvement – and became the foundations of our teaching at our violin institute. It was a unique privilege to learn from Suzuki and study at TERI. Takahashi’s classes were valuable for musical development.

Our daughter Phianne, also a violinist, soon entered the Suzuki Institute (kaikan) after a short time at a Japanese high school. Her graduation was a month or so after mine.

What we learned

- Perhaps the most important of all was kindness – especially towards children, and to others. Kindness was Dr Suzuki’s enduring quality, one that infused all his teaching.

- Suzuki’s teachings about the nature and origin of talent and ability deepened our understanding of learning and education. Learning how to use recordings and the value of sufficient right repetition were paramount in the development of relative mastery. 10,000 times practice became the norm, both for us and later for our students in the acquisition of skill and development of ability. The lessons we learned there provided the inspiration for the years ahead as we built our violin institute.

- We recognise the importance of the environment in which we live in all its aspects and how we can improve it to foster a happy and meaningful life.

- The value of memory: All the music we studied had to be performed from memory. This was somewhat of a challenge at first that soon became a lifelong habit. The great benefit of playing from memory is that it enables you to focus on musical expression more deeply – such as phrasing and articulation – and have a broader perspective of the whole piece. Later, our own students were also required to memorise everything.

- Friendly active cooperation – working together for everyone’s benefit – rather than competition.

- Persistence and endurance – never giving up.

We spent a lot of time observing Suzuki teachers at the Suzuki Institute (Kaikan), at summer schools and workshops, in Hirose’s Tokyo studio and others. At first we thought there was a unique Japanese way of teaching, yet after 3 and more years we realised Dr Suzuki and the other Japanese Suzuki teachers were demonstrating a universal way, applicable to all countries and cultures. What struck us was the non-competitive nature of high-level teaching and learning and the cooperative interaction of parents, students and teachers.

The environment of the Kaikan had a hugely positive influence on your playing and teaching, especially from watching and learning from the other kenkyusei. Daily practising together in the cacophony of the kenkyusei room was an interesting experience.

Everyone had to play at Monday Concert, a worthwhile challenge which eventually enabled us to perform with less stage anxiety.

The morning group classes were an unmissable experience of learning personally from Suzuki. In the 3 years or so we were there, Suzuki taught countless invaluable aspects of teaching and playing.

When it came time to produce a poem in calligraphy for my graduation, I spent a long afternoon repeating the poem over and over again, trying to satisfy the Shuji teacher with my efforts. It was getting dark when I explained that I’d need to return home. At this point the teacher looked along the long series I had drawn and chose one I had done hours earlier!

We studied musical expression and interpretation from several sources in Matsumoto: Takahashi’s excellent classes, Suzuki’s insights, recordings and ultimately from deep personal knowledge of the music through practice and performance. Later, more is learned through teaching.

There was a constant stream of visiting teachers and professional musicians, some who taught at workshops or performed at public concerts.

Watching and celebrating other students’ graduations was inspirational. There was a period of rapid progress prior to each graduation as the hours and months of extra work (practice) accumulate and blossom.

During my final year I work harder than ever. Practice time in the latter months expands to ten and ultimately twelve hours a day outside of classes. (Except for the last week, I still teach English in the evenings to support us.) It is exhilarating to be extended to the limit and to finally feel like I’m making real progress in my playing.

As the day approaches, I rehearse with the orchestra and accompanist two or three times each week. All is going well, until during one rehearsal just a week out from the concert, I make a nervy gaffe in the middle of the Bach concerto that I’d been playing well for over a year!

What is happening? I gloomily ride my bike home and ponder over my preparations. It doesn’t make sense. I know the music so well. Every note is an old friend. Every phrase a part of my being.

Eventually it dawns on me that I’m sometimes thinking ahead about a passage coming up – or reflecting on a section I have just played. I’m not living in the music as it’s happening.

During my next practice I resolve to just listen to the music as I play, and keep my attention in the present moment without wavering or wandering. It is easy to do for short periods of time, but invariably my thoughts veer off again to a difficult section ahead or back to an earlier one that could have been a little better.

Only after several hours of persistent concentration am I able to stay in the zone for longer periods.

As the following rehearsal I am more confident that I can stay focused. Happily, the rehearsal goes off without a hitch, as does the next ones and I sense I am on to something. It’s working.

All during the week I practise hard at keeping in the present.

Winter this year is particularly cold. There are heavy snowfalls and we sometimes have to struggle through a metre of snow to get to the institute. On the day of my concert the temperature goes down to -20°C, yet I love the cold, it revives me out of the years of hot Australian summers. Despite the heating in the concert hall, I have to immerse my hands in warm water before going on stage.

In the audience are all the other students, teachers, my family, friends and others. This is it – the pinnacle of my studies with Suzuki!

From that special moment, I walk on to stage in the space-time of now. When I begin playing, the sense of time disappears completely, and I am carried along on the river of music to the end of the concert. As the last notes of Beethoven’s Spring Sonata ring out in the auditorium, it feels as if the beginning and the end are connected, part of the same whole, an experience that affects me profoundly and I carry to this day.

The Suzuki institute ran virtually every day of the year, so to spend family time together we found it necessary to create a real weekend. In winter we occasionally went skiing in Hakuba, enjoyed the local festivals in summer and took day trips to the surrounding areas.

Summer school was an invaluable opportunity to watch Suzuki teachers from all over Japan. Mr. Hirose’s classes were a drawcard for me. We sometimes visited his classes in Tokyo.

The Budokan concerts were the showpiece of the year for students from all over Japan. The vast space made it difficult to coordinate the playing, but it was an unforgettable spectacle.

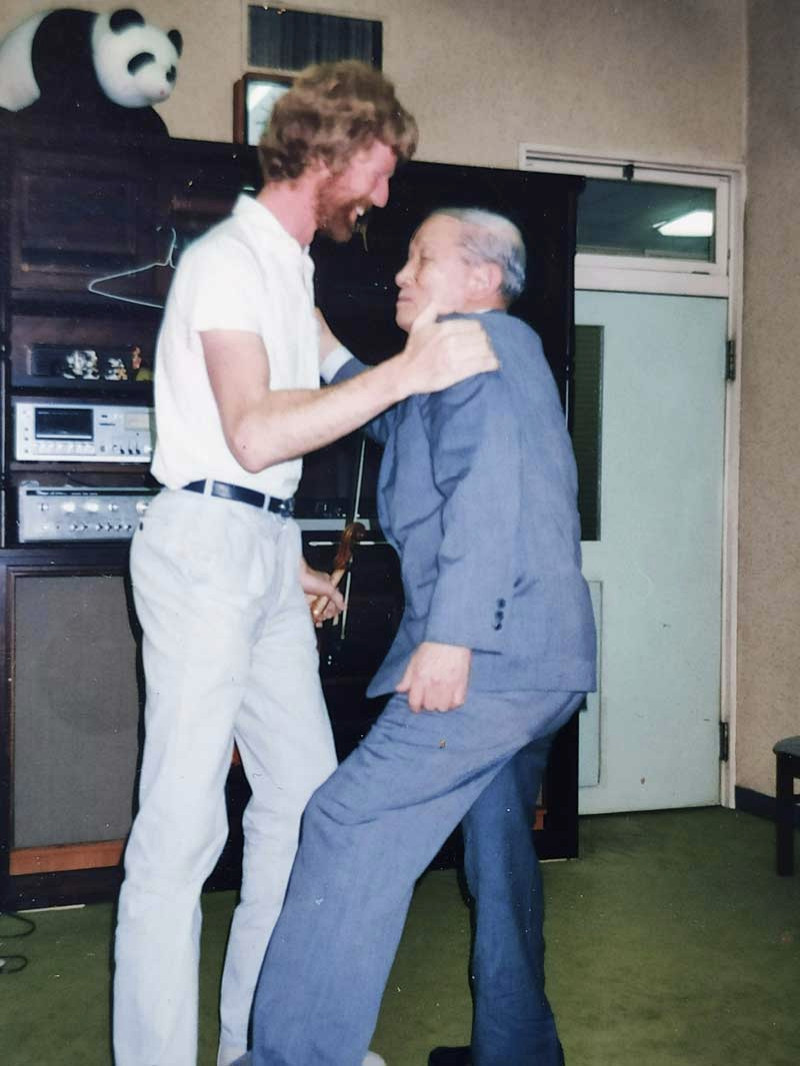

Dr. Suzuki was an exceptional person – teacher, educator, philosopher, and humanitarian. It was our privilege to know and learn from him.

The influence of this study in our lives and what we have done since then:

After a year teaching violin in England, we returned to Perth, Australia in late 1991 to set up our government accredited violin institute. At its zenith, we taught over 120 students with a staff of 6 teachers. Allie’s training and experience is particularly valuable in the group activities and goal setting sessions. Students graduate each year at the various Suzuki levels and advanced players graduated in Certificate IV, Diploma and Advanced Diploma in Violin and are qualified to enter, for example, the second year of a university music degree program.

It's gratifying to see many of our past students go on to become Suzuki teachers, concert performers, join orchestras or other musical groups and make music part of their lives.

In 2013 we began building our website, Teach Suzuki Violin, a membership platform providing help and guidance for teachers, students, and parents. The website covers practically every aspect of our work, including a detailed guide to the Suzuki violin repertoire plus solos and beyond, effective practice, violin technique, musicality, how to set up a studio, run successful group classes, teach beginners, organise concerts and many other topics. We’re grateful that the support it receives from member subscriptions enables it to continue and help others.

Our years in Japan have had a profound influence on all of our family, and not only in our teaching careers. The philosophical, educational, and cultural influences are permanently infused into our lives.Photos in Matsumoto

Lessons:

Kenkyusei room:

Group picture at Kaikan:

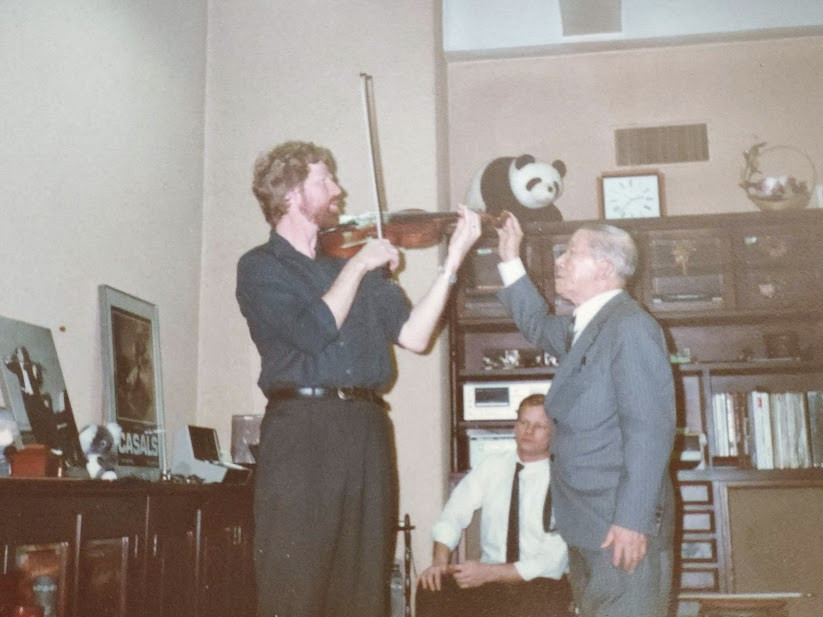

Graduation: