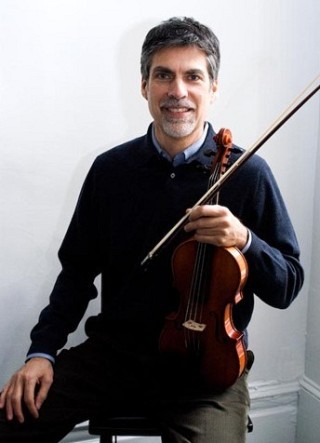

Allen Lieb

I was requested to reflect on my memories of studying with Dr. Suzuki in Matsumoto: specifically what were my main takeaways as it were, the journey in my personal studies, and what might have changed from my initial impressions to my departure from the Kaikan.

This will not be David Copperfield. But I do want to reflect on a few of Dr. Suzuki’s main tenets of Talent Education as they continue to affect me and give me a particular perspective in my life as a Suzuki student - so far.

I was fortunate to have had as good a grounding in the Suzuki approach and the Suzuki violin repertoire as I had before arriving in Matsumoto. I had begun some Suzuki teaching in undergraduate school in Memphis when the community-based Suzuki program in the city there was brought into the music department. Subsequently, I attended several Suzuki summer institutes that, unbeknownst to me at the time, were just in their infancy around the country. There I could observe and study with practically all the pioneer teachers of the movement in the United States and several from Europe. Following that, I attended graduate school with John Kendall for 2.5 years in a program where we were completely immersed at the String House in all things Suzuki Method. The summer of 1975, I attended the 1st International Suzuki Conference, in Hawaii, witnessing and participating in sessions with teachers from around the globe and, most importantly, with Dr. Suzuki himself. The enthusiasm and excitement at all these events among the participants was palpable. It was an era of discovery. I believe this is what sparked my thinking about going to study at the Talent Education Institute in Matsumoto.

Going to Matsumoto seemed a natural extension of study after finishing graduate school. My reasoning was that the founder of this movement was there, he was getting older (although then not much older than I am now!), and I had no reason not to go – at least in my very self-centered world-view. So I took my naiveté, my violin, two enormous suitcases, and a one-way plane ticket, and off I went to Japan.

What did I find when I got there? Well I found first that, in the immortal words of Dr. Suzuki, “All Japanese children speak Japanese!” Including the adults. I suddenly found myself as a foreigner in a completely different culture, not able to communicate, read nor write. Fortunately for me, I was surrounded by other foreign kenkyusei at the school and sympathetic members of the community who eased my transition into the life of this small country town surrounded majestically by the Japanese Alps. Being at Saino Kyoiku had some of the same feeling as being at the String House in Illinois. Our entire world at the Kaikan centered around activities involving Suzuki Method, and our studies there were singularly focused. What a terrifying feeling it was to stand on that recital hall stage for my first Monday Concert. I never fully got over that anxiety of performing every week in front of Dr. Suzuki and the other kenkyusei.

Lessons in Dr. Suzuki’s studio were master class style and in random order. Your lesson was as long as it was, depending on your specific assignments. Every lesson started with some form of a Tonalization. My first four months were spent on an open D string attempting to reshape my bow hold and my approach in connecting the bow to the string. My first impression in hearing everyone perform on the weekly Monday Concerts was that everyone had that tone - what Bill Starr had coined the Saino Kyoiku tone - the tone that had so captured the ears and attention of audiences first hearing the Suzuki Tour Group concerts.

Dr. Suzuki was relentless in his pursuit with everyone for an understanding of how to achieve that sound. After a time, I began to notice that some kenkyusei were more technically adept than others, but I remember clearly Dr. Suzuki’s comments about a student preparing for graduation: “She understands tone,” he said. “She will be able to teach her students well.” We are all familiar with his strong belief that, “Tone has a living soul.” And he actually meant that we all should understand how to do this in our own playing and how to teach it to our students. It means we can connect with their souls as human beings. And in order to affect change in others, we must be able to do that in ourselves.

Week after week in my abbreviated lessons, Dr. Suzuki would demonstrate both aurally and physically what he wanted. How many times did I hear, after I played my open D, struggling to balance my bow hold: “No. Please try again.” He played. I played. “No, this way is better.” And finally, “Please study more.” And so it went. I recall my intense frustration and, quite frankly, sometimes my anger with Dr. Suzuki during those first months, and my meager attempts to understand the physical nuances necessary to allow my bow and violin to speak with that sound. Did he sense this? I’m not quite sure. However, one day after a particularly intense session, he brought me a shikishi on which he had written on the back, “You don’t play violin! The bow plays the violin. You only help the bow.” What he added in person, but not in writing, was, “You help too much.”

But finally it did happen. I could actually feel the transition take place. I still retain the distinct memory of feeling that happening in my body and in the instrument during a frequently repeated Monday Concert performance of “La Folia.” I could see out of the corner of my eye that Dr. Suzuki had a slight smile. What a relief! And how freeing to feel myself a part of the violin speaking its true tone.

The Kaikan itself vibrated with the sense of dedication to the Talent Education idea. It was truly, to those involved, a movement in Japanese society. There was a real sense of mission and purpose from the teachers, the parents and even from the office staff. Of course most of this stemmed from Dr. Suzuki’s beliefs and his personal commitment to instilling change in society writ large. While he was a product of his own environment, he had been abroad in his formative years. Those experiences had a profound effect in formulating his ideas about the world. He had witnessed catastrophic events unfold in his own country that spurred him on in his mission to create a better way to nurture people’s hearts.

Dr. Suzuki would admonish audiences at concerts and conferences, filled with parents and teachers, to do better for the children and for themselves. At lessons, he would focus his energy on each of us and at graduation, require that we recite our dedication of purpose to him individually. But let’s all remember that he gave that legacy to everyone. None of us own the Suzuki Method except as it exists in ourselves. But what gives us more strength to move through the world is the collective energy we bring to this movement: in the way we rear the students and families in our care, and in our relationships with colleagues - both personal and professional.

I have a refrigerator magnet - a student gift - with a quote by the US President John Kennedy that says, “One person can make a difference, and everyone should try.” In our current world situation we can witness that for good and unfortunately for evil. Certainly Dr. Suzuki is our clearest example of what can happen for the good.

In closing, I relate another memory from my struggles in lessons to not just understand what Dr. Suzuki was asking me to do, but to actually demonstrate what I was supposed to understand. After he had finished repeated examples, I commented, “Yes, I know.” He looked straight at me and stated rather pointedly, “Yes, I know you know. Please do!”

And so we do, and remember, that commitment, care, empathy, excitement in discovery, the thrill of accomplishment not just in ourselves but also for others, beauty in the expression of an art form, belief in the ever-expanding possibility to achieve - these qualities are not exclusive to us in this movement, but they are integral and essential; and we can remember that.

Thank you again for giving me the opportunity to share these experiences and reflections that have lasted a lifetime - so far. And for giving me a place in the world with all of you.

—Allen Lieb

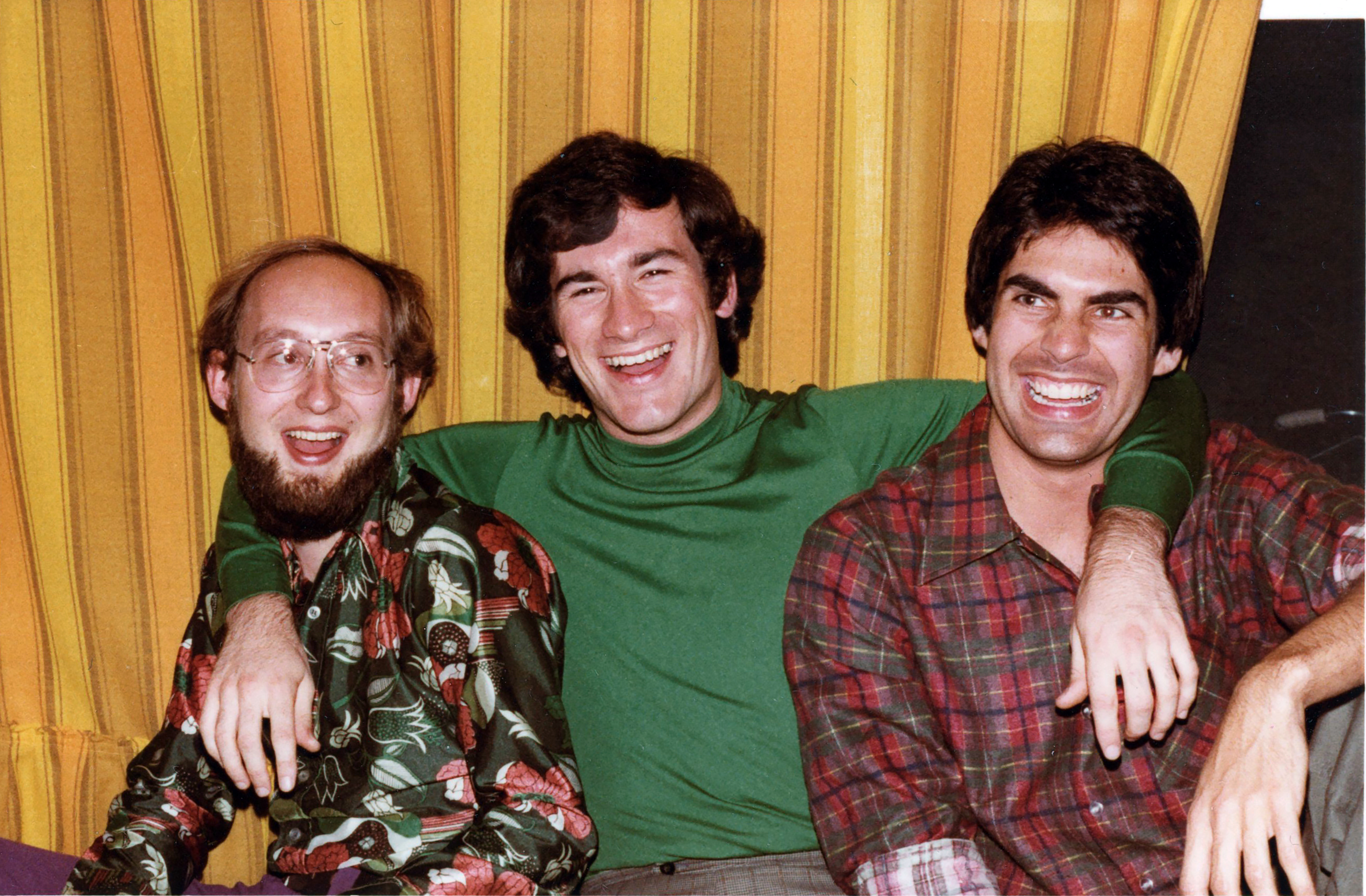

Photos in Japan

In my lesson with Dr. Suzuki (Craig Timmerman and Mary Monticone in the background) - 1977

Matsumoto Castle and my excellent bicycle - 1977

The Three Musketeers: Craig Timmerman, Christophe Bossuat, and me - 1977