Cathy (Catherine) Shepheard

Ms. Shepheard graduated from the Talent Education Institute in Matsumoto, Japan, in 1980, under the tutelage of Shinichi Suzuki. She pursued further violin and pedagogy study in Germany (Prof Igor Ozim, Helfried Fister) and Sydney, (Sydney Conservatorium Janet Davies, Christopher Kimber), and at short courses and master courses in Austria (Valery Klimov, Gésa Szilvay - Colour Strings). Interest in Alexander Technique principles developed into long-term learning about applied AT in violin playing (Janet Davies, Sydney Conservatorium).

As a Suzuki Teacher Trainer, Ms. Shepheard has taught in Australia and as an ESA Teacher trainer in Germany and Holland. She has taught at Suzuki Workshops and conferences in USA, UK, Europe, Australia, and NZ. She has also taught violin and String Pedagogy at tertiary institutions including Cologne Uni, Musik Hochschule Münster (Westfälischen Wilhelms Uni), and Robert Schumann Hochschule in Düsseldorf. As a guest lecturer/coach, she has taught at Monash Uni, Melbourne; Crete, Greece; Osnabrück und Wuppertal Musikhochschulen, Germany; and at chamber music camps in Victoria and NSW, Australia.

Ms. Shepheard has served as an adjudicator at competitions for violin and chamber music for ‘Jugend Musiziert’ in Germany, and as a violin examiner for the Australian Music Examination Board.

Orchestral and chamber music playing include performing with the Australian Opera and Ballet Orchestra, and in various chamber orchestras and ensembles in Münster, Düsseldorf, and Cologne, Germany, with tours in Europe.

She has held various positions at music schools in Germany and music departments in Australia (Head of Strings at Ascham Girls School in Sydney, Sydney Grammar School, and Sydney Conservatorium High School). She has been orchestra conductor for the Sydney Youth Orchestra group and at music camps in Australia and Germany. Her private teaching include pupils from age 2 and older, and former students are amateur musicians, music teachers, and orchestral players dotted around the globe.

She is currently teaching violin and viola pedagogy at the Robert Schumann Hochschule in Düsseldorf, Germany.

Other places lived since Japan: Melbourne, Tamworth, Sydney, and in Germany - Düsseldorf, Münster NRW, Cologne, Bacharach.

Instrument studied while in Japan: Violin

Dates in Japan to study with Shinichi Suzuki:

- (First meeting with Dr. Suzuki - 1967 in NewYork), Lessons in Matsumoto in Jan 1976.

- 2-year study duration in Matsumoto: January 1979 until Graduation date 12.12.1980.

- Visits to Matsumoto in 1981/82, 1983,1985, 1992, 1998 early January - I spoke to Mrs. Suzuki!

- Suzuki Conferences in Europe with Suzuki-sensei teaching : 1979 Munich, Germany; 1983 Hertsfordshire, UK; 1984 Landau, Germany; La Saulsaie, France

- 1987 Berlin, Germany

- Australian Pan Pacific Suzuki Conferences where Dr. Suzuki taught: 1989 Melbourne

Memories

Cathy Shepheard (August 2023)

Before I launch into my subject of choice, rather than give an account of my time at the Kaikan, I do want to acknowledge the wonderful time I had, and the wonderful friends I made there. I felt so safe and secure, and Suzuki-sensei’s support was never waning. Collectively working towards the same goal is a very special experience.

Suzuki-sensei’s approach for teaching young children was highly developed by the time I arrived in Matsumoto in early 1979 for an eventual two-year stay. His Mother Tongue concept within the ‘Suzuki Violin School’ had already proved to be very successful. He and his pool of violin teachers in Japan had forged ahead, building up a wealth of experience for us to marvel at and learn from.

Over the duration of my stay, I began to realise how very invested Dr. Suzuki was in the quintessential question - How does a player become musical? What does pure musicianship look like, or rather, sound like? AND how does one acquire this? How is this presented on the violin?

One ‘piece of the puzzle’ is undoubtably the skill on the instrument – the development and application of a ‘superior violin technique’ (minus any cold, mechanical connotations of the “technique” word, and embracing enlightened concepts, such as Suzuki-sensei’s ‘Tonalization’). Another is a growing knowledge of music theory and harmony. Yet another, is developing critical listening skills......Suzuki-sensei’s research into the power of the audible example and his results are known to us all. Teachers trained in his approach:

- Choose musical and violinistic templates that serve to build musical and violinistic knowledge, feed the imagination, and hone listening skills.

- Work regularly on their own playing and performance, for all good professional and personal reasons, and to maintain the function of ‘leading by example’ in the lesson.

Today, with YouTube and Spotify etc., we have a dilemma of choice, yet years ago (at least in Australia), it was difficult to obtain specific recordings. I was so grateful, when my Sydney Conservatorium violin teacher, Janet Davies, purchased a mildly scratched, second-hand record of Heifetz performing the Glazunov Concerto. This was a real ‘find’ at a flea market in the late eighties!

In Matsumoto we had a wonderful resource in Sensei’s collection of recordings in the kenkyusei room. Some of the Kreisler, Elman and Casals records were rather overused, but helpful kenkyusei brought in better copies, or made audio cassettes on request.

In 1979/80 one of the kenkyusei with the nickname of ‘Otōsan’, and real name of Kayo, was studying the César Franck Sonata. I was so taken with this work that I asked Suzuki-sensei if I, too, could learn it. He agreed, and my mother sent me her copy of the music in support of the idea, and to supply me with fingering and bowing options. In hindsight, I should have bought a new copy then, because by the time I was ‘finished’, I had no way of deciphering whose markings were whose, and now, after years of delving into historical violin schools and choices of fingerings, it would have been nice to have clarity. In any case, the Franck Sonata became part of my ‘Graduation Programme,’ alongside the fixed repertoire of that time. Humbly, I recall being graciously accompanied by Miss Junko Muto from Kyoto, not only on the piano, but also on strolls through temples and shrines, in between rehearsals.

At Sensei’s suggestion, I listened to Arthur Grumiaux while learning the Mozart G Major Concerto, Fritz Kreisler for the Mendelssohn Concerto, and now I was to listen to Jaques Thibaud and Alfred Cortot. I was supplied with a cassette of their 1923 recording. (The duo recorded the sonata again in 1929.) But at some point, I switched to Itzhak Perlman and Vladimir Ashkenazy. “Who is your teacher?” Sensei asked me, and I replied, “Perlman.” “Thibaud is very good. You can catch something from listening to his playing,” he added. Well, things became a little tangled, with me listening to Perlman and Ashkenazy while being expected to play along with Thibaud and Cortot in my lesson. It is hard to say how this situation even eventuated, except in the context of an 18-year-old leaning towards the performance of contemporary artists, on a shiny, new LP record. (Incidentally, the documentary about Ashkenazy produced by Christopher Nupen, has a lovely snippet of two brilliant, young performers discussing ‘takes’ of the Franck Sonata on their first recording collaboration, which took place at the Decca London studios in 1968.)

Years later, I finally got my hands on the recording of Shinichi Suzuki himself performing the Franck Sonata, which Japanese friends had referenced. The recording is from 1928, on the eve of his study period with Karl Klingler, and illustrates audibly Suzuki-sensei’s historical proximity to the romantic. The César Franck Sonata, composed in 1886, and hailed as a masterpiece from the beginning, was quite fresh repertoire at the time Suzuki studied it.

At 18, I was ignorant of all these credentials, and my ‘catching’ abilities at the time were woefully underdeveloped, but thankfully, I did turn back to Thibaud before I ‘graduated.’

After my Graduation Recital, Sensei singled me out in the kenkyusei group lesson to give me more advice on the Franck Sonata and tone colour, and before I left Japan, he made it crystal clear that I was to continue my violin studies – “Perhaps in Germany, where I studied,” he suggested, “Don’t just go back to Australia, and start teaching children!”

Over a decade of studying, teaching, and playing passed before I met my husband to be, violist, Hartmut Lindemann. Early on, I remember him being slightly impressed by my quick recognition of Oscar Shumsky’s playing. But at that point, he couldn’t have known how practised I was in recognizing the old players. Yes, I could recognize them, but Hartmut was light years ahead in understanding how each player was achieving an unmistakably personal sound and style. “Hartmut has very good ears!” Felicity Lipman marvelled, when she came to teach my pupils in Sydney in the 90’s.

At 14, Hartmut was a late starter, but he instantly became an avid listener of recordings of concert violinists and was drawn to Mischa Elman’s tone and expression (initially with Elman’s recording of Preghiera composed by Kreisler) at an early stage. He was intrigued by what makes a performance, or even just a particular tone quality or tone colour moving to him (Does this sound familiar?), and this ‘hobby’ intrinsically connected to his own performance and playing career became his research. “Essentially, I was self-taught, as almost everything I can do on my instrument, I learnt from listening to recordings” he recounts.

Hartmut’s ‘field’ stretches from the beginning of recorded sound to around the mid-20th Century. Combined with a love of and affinity to romantic music, he has secured a vast knowledge of the personal playing styles and musical tastes of the recording artists (in particular, string players) spanning this time. One focus is on identifying ‘expressive devices’ such as portamento, vibrato, tone colour, bow techniques etc. used in the musical expression of a particular performer, and then deciphering how the ‘expressive device’ is incorporated into the playing. Portamento, for instance, requires a choice of fingering, bow speed, tone colour and vibrato, agogic ....

Shinichi Suzuki’s deepest connection to western culture and classical music came from his lived experience of the early 20th century. He was in a musical environment of distinctive national schools of violin playing, and where each concert artist displayed and nurtured a uniquely personal playing style and sound. Suzuki had, therefore, a natural understanding and respect for this.

As Carlos María Solare points out, in a review from the 2008 January issue of The STRAD, Hartmut, too, has achieved such a uniquely personal sound.

“Hartmut Lindemann is a unique player, who has made a study of the technical and expressive vocabulary of the Old Masters (such as Heifetz, Elman, Menuhin and Primrose) and upon that basis developed an unmistakable style of his own. No one today – and I mean this literally – plays quite the way he does. Schumann’s Violin Sonata sounds in Lindemann’s own arrangement almost better than the original, which keeps the violin in its less sonorous register too much of the time....”

Hartmut maintains that he has had an advantage with performing repertoire on the viola because in the main, it has not been interpreted by the greatest masters with the exception of William Primrose, who may have produced the ultimate performance. Incidentally, Hartmut was flattered to hear that Koji Toyoda recommended ‘The Lindemann Series’ to his viola students in Matsumoto.

In my lifetime, musical taboos have come and gone. Outright rejection of listening to recordings as part of a musical learning process barely exists, and condemnation of salon pieces by Fritz Kreisler and others, as frivolous and musically worthless, now seems incongruous. The road that leads to authentic personalised sound and style, however, seems to need renewed attention! It concerns me to think that accuracy and reliability, masquerading as higher virtues, might become the goals in music, rather than aiming for true artistic integrity.

Thankfully, we have access to a wealth of extraordinary recordings that span well over 100 years. We also have a saturation of videos from the weakest hobby player through to the riveting performance of a little known or forgotten musician, so it is a challenge for all who are searching for special musical qualities. The importance of critical listening is certainly magnified, and the keen development of listening skills even more crucial.

In closing, wandering down memory lane, and penning some anecdotes and thoughts for this article, have given me the opportunity to reflect, yet again, on my very good fortune to have known Suzuki-sensei, and again to admire his tremendous foresight and legacy.

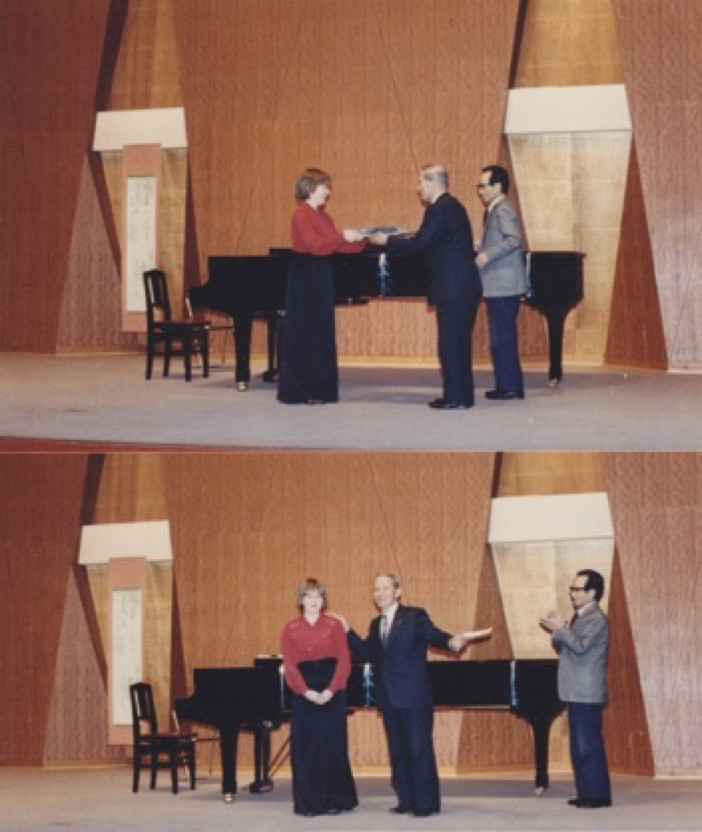

Photos in Matsumoto

First visit to Matsumoto for 2 weeks at 14 years of age

Graduation on 12.12.80 at 18 years of age